Art on the Line

With a gentle assist from Ansel Adams, Michael Eastman has become a nationally renowned photographer.

By Alexa Beattie / Portrait by Suzy Gorman / Photos by Michael Eastman

One of the first things St. Louis photographer Michael Eastman says is this: “I’m not an artist.” He is sitting at an impossibly long, gorgeously weathered wooden dining table in his house in University City. We are here to talk about a half-century of work, a storied career of putting his observations to “albumen.”

Michael Eastman in his office at the old Globe Democrat building, sitting in front of his photograph, “Red Window, Portland, 2011.”

“But I am A.D.D.”

He looks woebegone when he says this; a little ashamed. We’re beginning with his early life, how he jumped — like a lad in a schoolyard — from thing to thing, not really touching the ground in any surefooted way.

He grew up in Clayton, graduated from Clayton High School, bounced first to the University of Wisconsin, and then to a short-term teaching position at an inner city elementary school in Washington D.C.

Meanwhile, he listened to Miles Davis, played a bit of guitar. He was, he declares, a hippy doing hippy things. And then, a little later, he became a salesperson. He owned a couple of shops — a boutique called The Lower Half on Brentwood and an upscale leather store in Richmond Heights.

“It was boring,” he says.

It took some time, in other words, for Michael Eastman to find his jam. But then, like one of the horses in his beautiful book (Horses), he was “off to the races.”

Horse #14 by Michael Eastman.

Of course, Eastman’s equine subjects are not racehorses, but inhabit the wide-open plains and pleats of land between hills and mountain ranges. In the going-down sun (which is when he prefers to take the pictures), their bodies are bronze, their manes are molten gold. And their eyes — “those eyes” — can’t help but stir the soul.

Eastman calls them portraits.

“Standing before these magnificent creatures, it was as if someone was looking back.” He flips, lovelorn, through the pages of the book.

“Animals are wonderful,” he says, “but horses are truly mythical.”

Horse #40, Santa Fe by Michael Eastman.

Eastman took his very first photograph (a portrait of a “pretty young woman”) on a friend’s camera in 1972.

“It was an average picture of a pretty girl, but because she was pretty, so was the picture,” he says. He developed the photograph himself and was thrilled to finally have something he’d made “out in the world.”

He became a little obsessed, stealing to bed each night with Ansel Adams’ book on the Zone System – unlikely reading matter for a young man.

“I was a monk,” he says. “But I still couldn’t get it right.”

Lucky for Eastman, that was then. There were things called “operators.” He picked up the phone and asked for Adams’ number. (Why not? Why wouldn’t you go directly to the source?).

Adams, in Carmel, California, took the call and — over the span of about three minutes — gave him a few tips.

Referring to that brazen show of pluck, Eastman says, “I never felt I was less because of what others had achieved, but just that we were on the same road and they were simply further along it.”

Mirror Guild, Milan.

Fidel’s Stairway, Havana.

From 1972 until 2000, Eastman made his living in commercial photography (family portraits, etc.). His first piece of “real art” was hung in an informal gallery space at Washington U. in 1972. It was an egg study (the play of light and shadow around it) and it was listed at $40.

“One woman thought that amount was absurd,” Eastman says. “She laughed her way out of the gallery.” But back then, he explains, it was a lot of money for something which wasn’t considered art.”

Eastman’s Horses was published in 2003 but he has six books to his name. Among them, The Forgotten Forest (on Forest Park) and Vanishing America: The End of Main Street Diners, Drive-Ins, Donut Shops, and Other Everyday Monuments.

“I love decay – old signage and surfaces that tell stories.” In that regard, he adds, St. Louis makes for a very good subject. He says he does a lot of work around Gravois and Chouteau avenues, and MLK Drive.

Black and in Color, 1986 by Michael Eastman.

While every object in Eastman’s home is a work of art, the thing which stands out most (propped superfluously against the wall) is a 4-by-5-foot photograph called Isabella’s Two Chairs. Taken in Havana in 2000, it’s at once melancholy and joyous. Melancholy because the two chairs are old and so are the tumbledown walls around them; but joyous because there’s romance to the outsized crystal chandelier, and coquetry in the laundry line behind it — two ropes pegged with bright dresses and pretty pillowcases, drying (one could easily imagine) in a cone of sunshine coming down through a hole in the Vitrolite roof.

“It’s my favorite.”

Isabella’s Two Chairs by Michael Eastman.

Nowadays, the pricing for Eastman’s art looks a little different: Of four original 6- by-8-foot prints of Isabella’s Two Chairs, three were sold at galleries in New York and Paris, but one remains — in the William Shearburn Gallery on Skinker Boulevard. And yes, that’s right: The “tag” reads $48,000.

Over time, like lichen over stone, Eastman’s notoriety has spread; his art is now sold across the globe and has been hung in the hallowed halls of (among others) The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Art Institute of Chicago. He is nonchalant. Or perhaps just humble. One of his photographs recently appeared in a photo spread in Veranda magazine; he didn’t even know it.

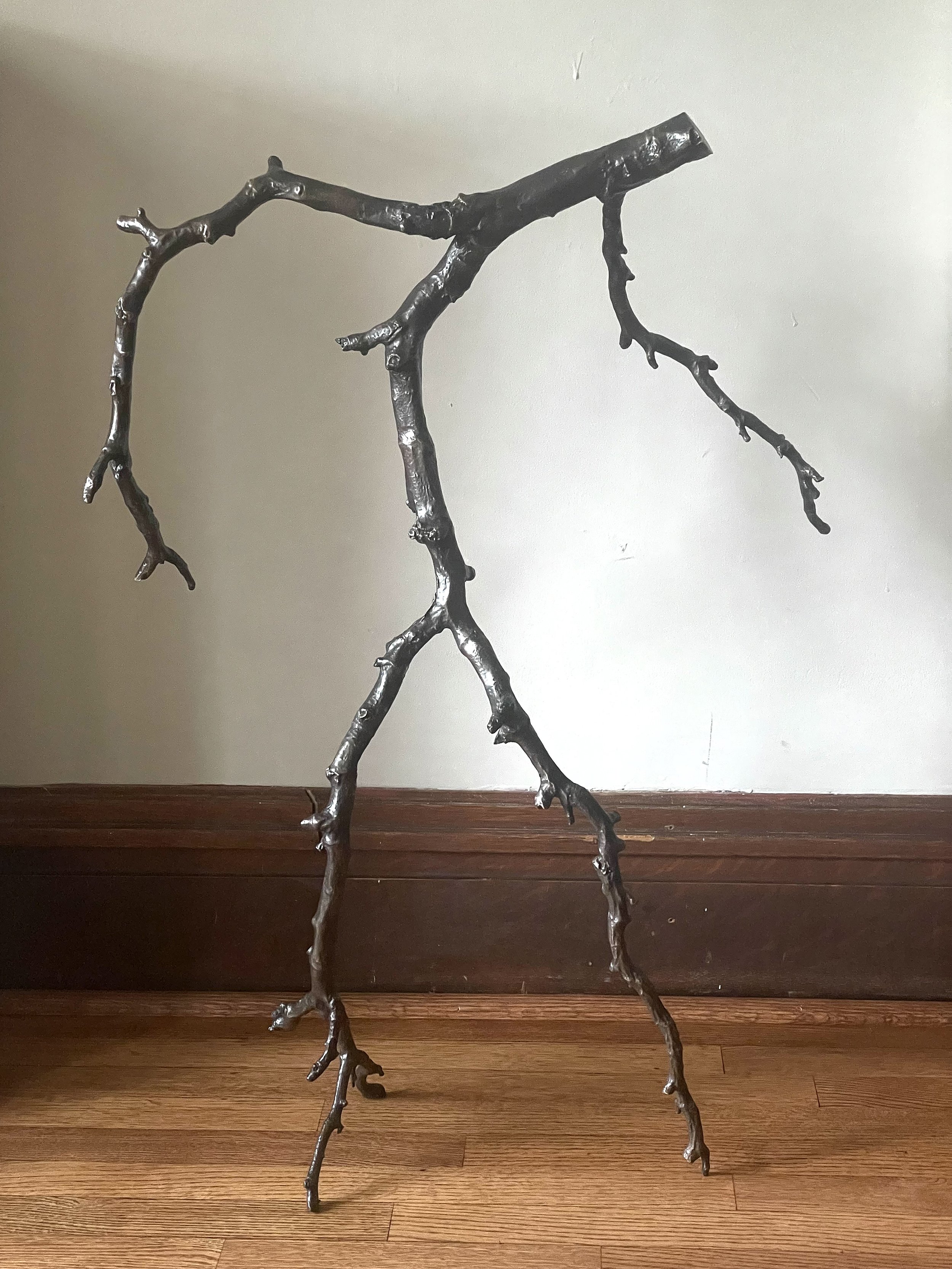

Twig #1 by Michael Eastman.

Eastman says he is proud to be a part of the St. Louis art community, which he readily describes as healthy, ever-evolving.

“The scene has changed a great deal since the ’70s of course,” he says. “But all for the better. We have first class galleries, a knowledgeable collector base; and our artists are as talented, committed and accomplished as any I have met.”

Shotgun House, New Orleans by Michael Eastman.

One of those artists, although master of a different medium, was novelist/essayist/short storyist and Wash. U. professor William Gass who lived directly across the street from Eastman. In such close proximity, in that leafy pocket between Clayton and Skinker, those two prolific men clearly were drinking the same water.

Four of Eastman’s books include essays by Gass. They were good friends until Gass’ death in 2017.

A tour of Eastman’s home, naturally ends in the basement, the “brains of the thing.” There’s an Inkjet printer down here the size of a sofa, banks of computers, and two ‘Mid-Mod’ Danish chairs which (were it not for Cuba, and “Isabella”) could seem out of place. But we know better. Inspiration often springs from the same source.

But there are also tiny things.

“It’s a new project,” Eastman says. He’s going over to some shelves. It’s hard to tell, at first, what exactly he’s heading for besides a menagerie of stick insects. And yes, they are sticks, picked off U. City sidewalks and the mossy paths of Forest Park, and nipped into animal or human shapes by a pair of small pliers (or his teeth). Some have been bronzed; some silvered. Others are left just as they came: Nature untouched.

Marcellas Resort, Benton Harbor by Michael Eastman.

Eastman wonders about this latest interest which, considering the profusion of these sublimely organic sculptures, could also be seen as a fixation.

“I think I’m saying something about the environment.” He looks forlorn again. “About preciousness.”

The Shearburn Gallery already has two 36-inch sticks in bronze. But, like Dreyfuss in Close Encounters, Eastman is already thinking bigger.

“I’m working on an eight-footer.”

So Eastman’s initial claim to not being “an artist” was absurd from the outset. For if turning the heart over (which his art does again and again) isn’t a hallmark of artistry, then what is?

“I just meant that when I started, I wasn’t that special,” he explains. “Photography was humble and real and honest. It wasn’t an institution, and there were no experts.

Eastman took Adams’ tips to his dark room, but still he was stumped.

“I did what he told me, but it didn’t work.”

So, without a second thought, Eastman called him back.

“I’m not quite getting it,” the “understudy” said. “I might need a little more.”

It was an even shorter conversation than the first: “Well, St. Louis,” Adams said, poised to nip the cord. “I don’t know what else to tell you.”